Episodic Falling Syndrome (Muscle Hypertonicity):

Cavaliers

Collapse Suddenly After Exercise

- What It Is

- Symptoms

- Diagnosis

- DNA Testing

- Treatment

- Similar Disorders

- Breeders' Responsibilities

- What You Can Do

- Research News

- Related Links

- Veterinary Resources

Episodic falling syndrome (EFS) is a unique genetic disorder in the cavalier King Charles spaniel, due to a mutation of its brevican gene (BCAN). The disorder has been recognized in the breed since the 1960s. No other breed is known to suffer from it, although it is categorized in a group of hyperkinetic movement disorders called paroxysmal dyskinesias. (The CKCS at right experiencing EFS is a ten-month-old. Courtesy, Dr. Boaz Levitin.)

The Animal Health Trust (AHT) reported that, as of May 15, 2012: 2,811 cavaliers had been DNA-tested for episodic falling syndrome, of which 104 (3.7%) were "affected" with two of the mutated EFS gene; 605 (21.52%) were "carriers" with only one of the mutated gene; and the rest, 2,102 (74.78%), were clear of the defective gene.

In a June 2012 report of DNA testing of 280 cavaliers, AHT researchers estimated that 19.1% of CKCSs are carriers of EFS, 35% of wholecolors (rubies and black-and-tans) are carriers, 0.3% of particolors (Blenheims and tri-colors) are affected with EFS, and 5.1% of wholecolors are affected.

RETURN TO TOP

What It Is

EFS is a non-progressive disorder that tends to improve with therapy, and the life spans of affected dogs do not appear to be shortened by the disease.

Veterinarians may refer to it as "episodic hypertonicity" or "hyperexplexia" or

"muscle hypertonicity" (and medically known as "paroxysmal exercise-induced

dystonia" or "dyskinesia"). Dystonia means an involuntary sustained

or intermittent contraction of a group of muscles, as to produce abnormal postures or twisting,

repetitive movements. Dyskinesia means diminished voluntary movements.

Paroxysmally refers to a sudden action, such as a spasm or convulsion, but not

continuously, followed by a return to normal behavior.

Veterinarians may refer to it as "episodic hypertonicity" or "hyperexplexia" or

"muscle hypertonicity" (and medically known as "paroxysmal exercise-induced

dystonia" or "dyskinesia"). Dystonia means an involuntary sustained

or intermittent contraction of a group of muscles, as to produce abnormal postures or twisting,

repetitive movements. Dyskinesia means diminished voluntary movements.

Paroxysmally refers to a sudden action, such as a spasm or convulsion, but not

continuously, followed by a return to normal behavior.

However, recent research (November 2010, July 2011, and January 2012) has established that EFS is not a muscular condition, but is due to a single recessive gene associated with brain function, a mutation of the BCAN gene, found only in cavaliers. As a result, affected puppies are more likely to be found in cases of line breeding or inbreeding on carrier bloodlines. (Photo at right is of Zano, a 9-year-old black-&-tan cavalier which has collapsed and paddled furiously while on his side.)

In many cases, EFS reportedly appears to occur immediately following certain specific activities, especially after those of physical exercise or other causes of excitement, such as running, chasing squirrels and birds. These are called "triggers".

Until 2010, EFS appeared to be a life-long condition of the cavaliers affected by it. However, research that year found that milder cases of EFS are more of a common condition in the CKCS, which tend to stabilize by age one year. EFS rarely is life-threatening. A July 2011 UK/US study found that, "carriers are extremely common (12.9%)." In a May 2012 report of DNA testing of 2,811 cavaliers, only 3.7% were affected with EFS, but another 21.52% were carriers of the EFS gene, which is nearly double the percentage predicted in the July 2011 study.

In a June 2012 report of DNA testing of 280 cavaliers, the UK's Animal Health Trust researchers estimate that 19.1% of CKCSs are carriers of EFS, 35% of wholecolors (rubies and black-and-tans) are carriers, 0.3% of particolors (Blenheims and tri-colors) are affected with EFS, and 5.1% of wholecolors are affected.

Some researchers have suggested that EFS in cavaliers may be associated with another disorder unique to the breed, called "idiopathic asymptomatic thrombocytopenia", an abnormally low number of blood platelets. Drs. Jens Häggström and Clarence Kvart of Sweden have noted in a 1997 article that thromboembolic events in the cerebral circulation of blood may be involved in EFS. See Blood Platelets for more information.

DNA testing is available to detect affected dogs and carriers. See our DNA Testing Section below.

RETURN TO TOP

Symptoms

Symptoms of EFS vary, but they all are attributed to the dog’s muscles being

unable to relax. Typical signs include the cavalier engaged in exercise or being

excited or stressed, and then suddenly develop a rigid gait in

the rear limbs,

extending and retracting in an exaggerated, stiff manner, like that of a hopping

rabbit. The dog’s back may be arched, and the dog often yelps. One or more limbs

may also protract excessively. (See the photo at left of a ruby cavalier in

the throes of arched protraction.) The dog may lose its footing while running. It

usually loses all coordination and collapses on its side or on its face. When

the cavalier collapses, it may hold its forelegs or hind paws over its head.

(See photo below). In some

instances, the cavalier’s symptoms follow a “deer-stalking” behavior, with its

head held close to the ground and its rear high in the air, as if stalking game.

In the most severe cases, the dog may hold its head so low that its hind

quarters somersault over its head. The affected cavalier may exhibit these

symptoms only when excited or stressed, but in some cases, the behaviors have

not been stress-induced. The dog may also overheat during an episode,

possibly due to an inability to pant.

the rear limbs,

extending and retracting in an exaggerated, stiff manner, like that of a hopping

rabbit. The dog’s back may be arched, and the dog often yelps. One or more limbs

may also protract excessively. (See the photo at left of a ruby cavalier in

the throes of arched protraction.) The dog may lose its footing while running. It

usually loses all coordination and collapses on its side or on its face. When

the cavalier collapses, it may hold its forelegs or hind paws over its head.

(See photo below). In some

instances, the cavalier’s symptoms follow a “deer-stalking” behavior, with its

head held close to the ground and its rear high in the air, as if stalking game.

In the most severe cases, the dog may hold its head so low that its hind

quarters somersault over its head. The affected cavalier may exhibit these

symptoms only when excited or stressed, but in some cases, the behaviors have

not been stress-induced. The dog may also overheat during an episode,

possibly due to an inability to pant.

See

video examples of EFS episodes on

YouTube here.

See

video examples of EFS episodes on

YouTube here.

The cavalier does not lose consciousness during the episodes, and mentally, it remains normal. Technically, the collapse is not a seizure, although it may be appear as one. The CKCS appears to know what is happening to it, and sees clearly, but loses control of its body. Afterwards, in most instances the dog recovers relatively quickly; it stands up and acts as if nothing unusual had occurred. However, if the cavalier exercises again immediately after recovery, it may induce another episode.

(About the photo at right, Dr. G. D. Shelton writes: "An 11-month-old male Cavalier King Charles Spaniel during an episode of hypertonicity. This figure shows the classically described positioning of the paws over the head. The dog was completely hypertonic at this time and collapsed.")

Also, some severely affected cavaliers have been known to lapse into repeated, lengthy episodes of the syndrome, and may even suffer permanent neurological injuries and not be able to recover from the attacks. At least a few CKCSs are known to have been euthanized to avoid continued suffering from the disorder.

It is to be distinguished from presyncope, another disorder to which cavalier King Charles spaniels are predisposed, which has some of the same symptoms. Syncope in cavaliers is associated with late stages of mitral valve disease. For more information on syncope and presyncope in CKCSs, see Mitral Valve Disease and Syncope.

RETURN TO TOP

Diagnosis

Episodic falling syndrome is the result of a single recessive gene mutation associated with neurological function. Until 2010, EFS had been believed to be a type of metabolic muscle disorder. The ages of cavaliers studied with EFS have varied from two months to four years. Both male and female CKCSs are affected.

The dogs are neurologically normal between episodes. Electromyographic evaluation detects the muscles at rest and engaged in no abnormal spontaneous activity. There is no evidence of heart or respiratory problems during the episode or the collapse. Blood tests, spinal fluid analysis, muscle biopsies, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain have not proved to be helpful in diagnosing the syndrome. Diagnosis, therefore, has been based solely upon the symptoms of the episode.

Since some of the symptoms of EFS are similar to other disorders, such as liver shunt, an epileptic seizure, or syringomyelia, the examining veterinarian may mis-diagnose the episodes and unnecessarily screen the dog for those other maladies. The primary differences between EFS and other disorders are that they usually are induced by exercise, excitement, stress, or apprehension; the EFS-affected dog remains conscious during the episodes; and the dog rarely will experience any continuing pain or discomfort.

Therefore, video recordings of the dog’s EFS episodes are helpful to the veterinarian in diagnosing the disorder. If a video device is not available, the owner should write a precise report of the Cavalier’s behaviors during the episode, to avoid mis-diagnosis, needless testing, and treatment with drugs which may inadvertently aggravate the condition.

In a brief July 2009 article, UK researchers Dr. Richard J Piercy and Gemma Walmsley disclosed that they had identified a genetic form of muscular dystrophy in the cavalier, with symptoms (weakness and exercise intolerance) similar to some of those of EFS. However, these other symptoms of this muscular dystrophy may clearly distinguish it from EFS: muscle atrophy, difficulty swallowing, and an enlarged tongue. Also, the researchers have found that only males are affected by this form of muscular dystrophy, and the females are only carriers of the mutation.

RETURN TO TOP

DNA Testing

In 2011, two UK research groups (see below) independently developed DNA swab

tests for detecting a recessive gene associated with brain function, the

brevican gene (BCAN), which, when mutated, is the cause of episodic falling disorder in the

CKCS. EFS is inherited as a autosomal recessive trait. If a DNA-tested cavalier is found to not have the mutated BCAN

gene, then it is "clear" of EFS. If the dog is found to have two of the mutated

gene,

In 2011, two UK research groups (see below) independently developed DNA swab

tests for detecting a recessive gene associated with brain function, the

brevican gene (BCAN), which, when mutated, is the cause of episodic falling disorder in the

CKCS. EFS is inherited as a autosomal recessive trait. If a DNA-tested cavalier is found to not have the mutated BCAN

gene, then it is "clear" of EFS. If the dog is found to have two of the mutated

gene,

then it is "affected" and has EFS, whether it shows symptoms or not. If

the dog is found to have only one of the mutated gene, then it is not affected

but is "a carrier".*

then it is "affected" and has EFS, whether it shows symptoms or not. If

the dog is found to have only one of the mutated gene, then it is not affected

but is "a carrier".*

*Despite the studies distinguishing dogs with a pair of the mutated genes as "affected" and dogs with only one of those genes as "carrier", there have been clinical reports that some carriers display symptoms of EFS.

Researchers led by Dr. Robert Harvey of the London School of Pharmacy, Dr. Leigh Anne Clark (Clemson) and Dr. Diane Shelton (Univ. Cal. at San Diego) (email gshelton@ucsd.edu) have identified the underlying genetic defect causing EFS in cavaliers. They found:

"Consistent with the unique clinical observed in affected dogs, we discovered that a homozygous microdeletion affecting BCAN is associated with EFS in CKCS dogs, confirming that this disorder is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. This mutation was not detected in control DNA samples from 54 other dog breeds, confirming the unique nature of this genomic rearrangement. ... Wider testing of a larger population of CKCS dogs without a history of EFS from the USA revealed that carriers are extremely common (12.9%). The development of molecular genetic tests for the EFS microdeletion will allow the implementation of directed breeding programs aimed at minimizing the number of animals with EFS and enable confirmatory diagnosis and pharmacotherapy of affected dogs."

See the January 2012 report here for details.

The knowledge of whether a cavalier is clear, affected, or a carrier of EFS is important to the responsible breeder who wants to avoid passing EFS to future generations in her bloodline of cavaliers. See Breeders' Responsibilities below for additional information about how to use the results of DNA testing to choose breeding partners.

Genetic testing laboratories which test for this mutation causing CDM include:

• American Kennel Club (AKC)

• Canine Genetic Diseases Network, University of Missouri

• Canine Genetic Testing (CAGT), University of Cambridge Dept. of Veterinary Medicine

• DDC DNA Diagnostics Center

• Dog Breeding Science (Australia)

• Embark, Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine

• GenSol Animal Diagnostics

• Laboklin

• MyDogDNA, Wisdom Panel

• Orivet

• Paw Print Genetics

• Veterinary Genetics Laboratory, University of California - Davis Veterinary Medicine

![]() Watch

this YouTube video to learn how to properly use a swab to obtain DNA from

your dog. See our Genetic Testing webpage for

more information about DNA testing.

Watch

this YouTube video to learn how to properly use a swab to obtain DNA from

your dog. See our Genetic Testing webpage for

more information about DNA testing.

RETURN TO TOP

Treatment

- Diazepam (Valium)

- Clonazepam (Klonopin, Rivotril)

- Acetazolamide (Diamox)

- Fluoxetine (Prozac, Zactin)

- Levetiracetem (Keppra)

- Vitamin E, tryptophan

- Chiropractic

- Diet

- Triggers

During

and after an episode, consider trying to comfort the dog by holding it gently.

Do not force the dog's legs to assume any position. Keep the dog as cool as

possible, and allow it to rest as much as it wishes after the episode.

During

and after an episode, consider trying to comfort the dog by holding it gently.

Do not force the dog's legs to assume any position. Keep the dog as cool as

possible, and allow it to rest as much as it wishes after the episode.

If you find that the dog has EFS episodes only after engaging in certain specific activities -- such as being overly excited about something or someone -- try to avoid those activities.

Until recently, no medications appeared to remedy the condition, and there was no known effective treatment. Affected dogs have not been found to respond to anticholinesterases. Phenobarbital (Epiphen, Soliphen, Solfoton, Luminal, Phenoleptil), a barbiturate, frequently is prescribed.

• Diazepam (Valium)

Some temporary improvement has been observed following treatment with a benzodiazepine drug called diazepam (Valium).

• Clonazepam (Klonopin, Rivotril)

In a study concluded in 2002, a

group of affected cavaliers was treated with another benzodiazepine drug,

clonazepam (Klonopin, Rivotril), which is a drug used to treat humans for

hereditary hyperexplexia or hyperekplexia ("startle disease"). Both diazepam and

clonazepam enhance gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmission. However, clonazepam is more potent

than diazepam in equivalent doses, and clonazepam has more anti-convulsant

effects. In the 2002 study, with clonazepam treatment (at 0.5 mg/kg tid), the

episodes decreased in frequency from between 25 and 30 per week to as few as one

every two to three months. After two years of treatment with clonazepam, dogs in

the study were described as clinically normal. It has

been

reported that CKCSs tend to be less responsive

to diazepam than other breeds, but that cavaliers can

markedly improve with clonazepam.

been

reported that CKCSs tend to be less responsive

to diazepam than other breeds, but that cavaliers can

markedly improve with clonazepam.

Dr. Jacques Penderis (right) has found that although some cavaliers initially respond well to treatment with clonazepam or diazepam, the dogs tend to develop tolerance to the drugs after a while and the beneficial effect wears off. Dr. Penderis states that the current treatment options for CKCSs with episodic falling syndrome are extremely limited.

• Acetazolamide (Diamox)

In cases that do not respond to clonazepam and where the episodes are not particularly severe or frequent, it may be best to accept the collapse episodes and try to identify and avoid events or stressors that may trigger the episodes. In severe cases, treatment can be tried with acetazolamide (Diamox), which is a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor which has shown some efficacy in autosomal dominant hyperkalemic periodic paralysis. Use of acetazolamide must only be done under careful veterinary supervision, and a number of dogs do not appear to tolerate the drug very well.

In a January 2017 review of involuntary movements in dogs -- paroxysmal dyskinesias -- the authors stated:

"In dogs, successful treatment of PNKD [paroxysmal nonkinesigenic dyskinesia] has been reported, albeit uncommonly, with clonazepam, acetazolamide and fluoxetine. Acetazolamide was also very effective in the management of EFS in Cavalier King Charles spaniels."

• Fluoxetine (Prozac, Zactin)

In a 2015 abstract, French researchers report that Fluoxetine (Prozac, Zactin), a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, was successful in treating two cavaliers with EFS and three Scottish terriers with Scotty cramp, resulting in early and long term remission of the symptoms.

• Levetiracetem (Keppra)

Levetiracetam (Keppra) is an anticonvulsant which can also be used in conjunction with phenobarbital and/or potassium bromide. it appears to be relatively safe for dogs, and reportedly rarely has any adverse side effects and does not appear to affect the liver or liver enzymes.

• Vitamin E, tryptophan

Vitamin E and tryptophan reportedly may decrease the frequency and severity of episodes. However, tryptophan (tryptophan hydroxylase 1) can increase serotonin levels, and a high level of serotonin is a suspected cause of early-onset mitral valve disease in the CKCS.

• Chiropractic

Periodic chiropractic treatments may be able to minimize an affected dog's symptoms of EFS.

• Diet

As far as we know, no veterinary literature has studied, or at least found, that specific diets have an effect on cavaliers diagnosed with EFS. Since a mutation of the brevican gene (BCAN) has been associated with EFS, it remains to be determined if any nutritional or gastrointestinal relationships exist with that mutation.

• Triggers

A way to prevent episodes of EFS in many affected dogs is to avoid activities which appear to trigger the episodes, such as excessive exercise, excitement, or stress. Try to keep the dog calm and avoid situations which may bring about fear, anxiety, prey drive, or a sense of being rushed.

RETURN TO TOP

Similar Disorders

Other disorders with almost the same symptoms include:

• Canine Epileptoid Cramping Syndrome (CECS), also known as Spikes Disease: This is most common in border terriers and Yorkshire terriers and very rarely in cavaliers.

• Scottie Cramp: The clinical signs of EFS are very similar to this disorder in Scottish terriers.

Due to the similarity of signs and symptoms of these disorders, EFS may be mis-diagnosed in cavalier cases in which th BCAN mutation is not detected.

RETURN TO TOP

Breeders' Responsibilities

Breeders

should have DNA tests performed on all cavalier breeding stock before

matings. See our DNA Testing Section for more

information about the available DNA testing programs.

Breeders

should have DNA tests performed on all cavalier breeding stock before

matings. See our DNA Testing Section for more

information about the available DNA testing programs.

• Breeding decisions using DNA results

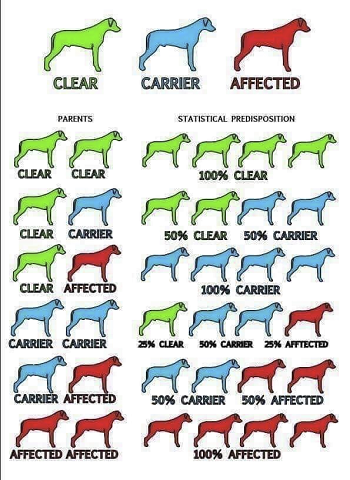

• If two clear cavaliers are mated, all offspring likewise should be clear of EFS.

• If a clear cavalier is mated to a carrier, each puppy has an equal (50%) chance of being clear or carrier. However, the outcome for each puppy is independent of all the other puppies so in any particular litter one might not necessarily get half clears and half carriers.

• If two carriers are mated, each puppy has a 50% chance of being a carrier, and a 25% chance of being either affected or clear, the outcome for each puppy being independent of all the other puppies.

• If a carrier and an affected are mated, each puppy has an equal (50%) chance of being affected or carrier, the outcome for each puppy being independent of all the other puppies.

• If two affecteds are mated, all puppies in the litter should be affected.

Obviously, it would be preferable to mate only clear cavaliers to each other. But if a cavalier breeder finds that one of her breeding stock is a carrier, she should mate that dog only to a clear cavalier. Then, once the litter is produced, the breeder should DNA-test the puppies to identify which ones are clear and which are carriers, and remove the carriers from the breeding program.*

* Read the UK Animal Health Trust's article on "Should We Breed Carriers?" by Dr. Cathryn Mellersh here.

Two carriers should not be mated to each other, and, of course, no affecteds should be mated at all.

If a breeder DNA-tests her breeding stock for the mutated gene causing EFS and then follows the above breeding protocol, she could eliminate all EFS-carriers from her bloodline within two generations.

As of February 2013, the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Club, USA recommends that its members/breeders comply with this breeding protocol.

RETURN TO TOP

What You Can Do

If you suspect your cavalier has this disorder, have the dog's DNA tested. See our DNA Testing Section for details.

RETURN TO TOP

Research News

July 2024:

European geneticists and neurologists sum up episodic

falling syndrome in cavaliers.

In a

July 2024 article, Netherlands and

UK geneticists and neurologiats (Paul J. J. Mandigers [right], Koen M.

Santifort, Mark Lowrie, Laurent Garosi) provide a review of various

paroxysmal dyskinesias (PDs), including episodic falling syndrome (EFS)

in cavalier King Charles spaniels. Their summary of EFS is as follows:

In a

July 2024 article, Netherlands and

UK geneticists and neurologiats (Paul J. J. Mandigers [right], Koen M.

Santifort, Mark Lowrie, Laurent Garosi) provide a review of various

paroxysmal dyskinesias (PDs), including episodic falling syndrome (EFS)

in cavalier King Charles spaniels. Their summary of EFS is as follows:

"Episodic falling syndrome (EFS) was first described in 1983. Affected dogs present themselves with progressive hypertonicity of the limbs leading to a characteristic “deer-stalking” or “praying” position. Other clinical signs may include facial muscle stiffness, stumbling, a “bunny-hopping” gait, arching of the back, and vocalization. The episodes, triggered by exercise, stress, apprehension, or excitement, last from less than 1 min to several minutes. It is the first PD in which the causative mutation was identified. It affects young dogs (up to 4 years) and is caused by a mutation in the brevican gene (BCAN). This gene encodes a brain-specific protein of the extracellular matrix proteoglycan complex. The abnormally formed protein results in a disrupted axonal conduction/synaptic stability. The mode of inheritance is autosomal recessive. Although all CKCS fur color variants can be crossed among each other, EFS was predominantly seen in the Ruby and Black and Tan fur variants, as the mutated allele had a higher frequency in these fur colors. Interestingly, EFS improves with age which might suggest that in time compensatory pathways may lead to a resolution of the abnormally formed protein (9, 18). For this reason, if affected CKCS only have a low frequency of these episodes, the advice could be to avoid triggers and show some hesitance in medical treatment. Affected CKCS have been treated with both clonazepam and acetazolamide (17). This PD can be classified as a PNKD [paroxysmal non-kinesigenic dyskinesia]."

March 2021:

ECVN Consensus Statement confirms episodic falling syndrome in

cavaliers and a mutation of their BCAN gene.

In

a

March 2021 Consensus Statement issued by the European College of

Veterinary Neurology (ECVN), authors Sofia Cerda-Gonzalez (right),

Rebecca A. Packer, Laurent Garosi, Mark Lowrie, Paul J. J. Mandigers,

Dennis P. O'Brien, and Holger A. Volk recommended standard terminology

for describing various movement disorders in canine breeds, with an

emphasis on paroxysmal dyskinesia, as well as a preliminary

classification and clinical approach to reporting cases. As an example

of such disorders, they singled out "deer stalking" in cavalier King

Charles spaniels. They classified "episodic hypertonicity" in cavaliers

as an inherited or presumed inherited primary paroxysmal dyskinesia,

with the "colloquial name" of episodic falling syndrome (EFS). They

classified cavailers as the "primary affected breed" of EFS and that its

mode of inheritance is "autosomal recessive", triggered by "exercise,

excitement, stress", with a duration of "<1 to several minutes", and a

progression of "improve/stabilize with age". Finally, the panel

confirmed that for the cavalier, the known genetic mutation is in the

BCAN gene.

In

a

March 2021 Consensus Statement issued by the European College of

Veterinary Neurology (ECVN), authors Sofia Cerda-Gonzalez (right),

Rebecca A. Packer, Laurent Garosi, Mark Lowrie, Paul J. J. Mandigers,

Dennis P. O'Brien, and Holger A. Volk recommended standard terminology

for describing various movement disorders in canine breeds, with an

emphasis on paroxysmal dyskinesia, as well as a preliminary

classification and clinical approach to reporting cases. As an example

of such disorders, they singled out "deer stalking" in cavalier King

Charles spaniels. They classified "episodic hypertonicity" in cavaliers

as an inherited or presumed inherited primary paroxysmal dyskinesia,

with the "colloquial name" of episodic falling syndrome (EFS). They

classified cavailers as the "primary affected breed" of EFS and that its

mode of inheritance is "autosomal recessive", triggered by "exercise,

excitement, stress", with a duration of "<1 to several minutes", and a

progression of "improve/stabilize with age". Finally, the panel

confirmed that for the cavalier, the known genetic mutation is in the

BCAN gene.

August 2020: The Animal Health Trust discontinued its DNA testing services as of July 31, 2020. The former staff of the AHT's canine genetics research office, led by Dr. Cathryn Mellersh, are planning to to open a new DNA testing service. For more information about this, go to the Canine-Genetics website.

January 2017:

UK researchers rate successful medications for Episodic Falling

Syndrome in CKCSs. In a

January 2017 review of involuntary movements in dogs -- paroxysmal

dyskinesias -- a pair of UK researchers (Mark Lowrie, Laurent Garosi

[right])

report that:

January 2017:

UK researchers rate successful medications for Episodic Falling

Syndrome in CKCSs. In a

January 2017 review of involuntary movements in dogs -- paroxysmal

dyskinesias -- a pair of UK researchers (Mark Lowrie, Laurent Garosi

[right])

report that:

"In dogs, successful treatment of PNKD [paroxysmal nonkinesigenic dyskinesia] has been reported, albeit uncommonly, with clonazepam, acetazolamide and fluoxetine. Acetazolamide was also very effective in the management of EFS in Cavalier King Charles spaniels."

November 2016: 12.3% of Belgium cavaliers are estimated to be episodic falling syndrome carriers. In an October 2016 report, a team of Belgian researchers (E. Beckers, M. Van Poucke, L. Ronsyn, Luc Peelman) found 12.3% of 57 cavalier King Charles spaniels were carriers of the episodic falling syndrome mutation. None of the 57 CKCSs were found to carry the homozygous mutation. They recommend "routine genotyping in breeding dogs because of the high frequency."

July 2016:

British researchers summarize episodic falling syndrome in

cavaliers.

In a

July 2016 article by British researchers (Mark Lowrie [right], Laurent

Garosi) about canine paroxysmal movement disorders in Labrador

retrievers and Jack Russell terriers, they also have neatly summarized

the current status of research about episodic falling syndrome (EFS) in

cavaliers. They state:

In a

July 2016 article by British researchers (Mark Lowrie [right], Laurent

Garosi) about canine paroxysmal movement disorders in Labrador

retrievers and Jack Russell terriers, they also have neatly summarized

the current status of research about episodic falling syndrome (EFS) in

cavaliers. They state:

"In dogs, the first genetically mapped PD [paroxysmal dyskinesia] was that associated with EFS [episodic falling syndrome] in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (Forman et al., 2012; Gill et al., 2012). The mutation was characterised as a deletion affecting the brevican gene (BCAN) which encodes a brain-specific component of the extracellular matrix proteoglycan complex. It is thought to be involved in homeostasis and mutations of this protein result in a disruption of axonal conduction and synaptic stability. An interesting observation in EFS is that the condition is self-limiting in some cases (Forman et al., 2012). It is suggested that compensatory pathways involving up regulation of other proteoglycans may occur and account for this rectification. Dogs in our study also seemed to show this improvement with age so a similar compensatory mechanism may be considered."

December 2015: Fluoxetine treatments successfully treat two CKCSs in a French study. In a September 2015 abstract before the ESVN-ECVN, French researchers (T. Bouzouraa, C. Escriou) report that Fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, was successful in treating two cavaliers with EFS and three Scottish terriers with Scotty cramp, resulting in early and long term remission of the symptoms.

November 2015:

Neurologists summarize research status of episodic

falling syndrome in cavaliers.

In a

November 2015 article, a team of

German and UK veterinary neurologists (Angelika Richter, Melanie Hamann,

Jörg Wissel, Holger A. Volk) researching paroxysmal dyskinesias briefly summarized the present

status of episodic falling syndrome (EFS) in cavalier King Charles

spaniels as:

In a

November 2015 article, a team of

German and UK veterinary neurologists (Angelika Richter, Melanie Hamann,

Jörg Wissel, Holger A. Volk) researching paroxysmal dyskinesias briefly summarized the present

status of episodic falling syndrome (EFS) in cavalier King Charles

spaniels as:

"Episodic falling in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (CKCS), an autosomal-recessive inherited disorder, shares similarities with human paroxysmal dyskinesia. In affected dogs, exercise and excitement can precipitate episodes of abnormal gait and fallings which last up to several minutes. There are no signs of an impairment of consciousness or autonomic dysfunction during or after these attacks. Affected animals develop an increased extensor muscle tone of all four limbs, resulting in an immobilized, 'deer-stalking'or 'praying' position, sometimes falling with legs held in extensor rigidity. Other clinical signs are facial muscle stiffness, stumbling, a 'bunny-hopping' gait, and arching of the back. It is unclear if cocontractions of flexors are involved. Initial clinical signs of the disease typically appear between 3 and 7 months of age. Interestingly, in some cases, there is spontaneous remission, as sometimes observed in human paroxysmal dyskinesia. There is no evidence for metabolic alterations as a cause, and light microscopic examinations have not revealed any lesions in the CNS or peripheral nerves. Clonazepam may be effective in suppressing the episodes in some cases. Recently, a 15.7 kb deletion in BCAN, encoding the brain-specific extracellular matrix-proteoglycan brevican, was found to be associated with episodic falling in CKCS. This protein plays an important role in cell adhesion, migration, axon guidance, and neuronal plasticity. How this mutation leads to the manifestation of this hyperkinetic movement disorder in dogs has yet to be unraveled."

July

2013:

CKCSC,USA adopts the episodic falling syndrome DNA testing scheme

as a

recommended breeding practice. At its February 21, 2013 board of

directors meeting, the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Club, USA adopted the

DNA breeding protocol for episodic falling syndrome (and also for

curly coat syndrome), as a "recommended breeding

practice."

July

2013:

CKCSC,USA adopts the episodic falling syndrome DNA testing scheme

as a

recommended breeding practice. At its February 21, 2013 board of

directors meeting, the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Club, USA adopted the

DNA breeding protocol for episodic falling syndrome (and also for

curly coat syndrome), as a "recommended breeding

practice."

April 2013: UK's Kennel Club adopts the DNA testing scheme for episodic falling syndrome in the CKCS. Finally, the UK Kennel Club has announced that it has approved the DNA testng scheme for episodic falling syndrome (and also for curly coat syndrome) in the cavalier breed. Details on the KC's website here.

March 2013: UK cavalier clubs urge Kennel Club to include Episodic Falling DNA test in KC's registration system. The UK cavalier clubs' Cavalier Health Laison Committee voted to ask the UK Kennel Club to include all results from the Episodic Falling (EF) and Curly Coat (DE/CC) DNA tests in the KC’s registration system and in its Health Test Results Finder. Furthermore the Clubs requested that all cavaliers be tested for both EF and DE/CC prior to breeding and that at least one parent of each litter is free of each mutation, to ensure no affected puppies can be produced or registered.

August 2012: VetGen offers DNA test for episodic falling syndrome in cavaliers. Veterinary Genetic Services (VetGen) now offers test kits for identifying the genetic defect causing episodic falling syndrome in cavaliers. VetGen's website for ordering the test kit is here.

June 2012: UK's Animal Health Trust estimates 19.1% of CKCSs are EFS carriers. The Animal Health Trust has issued its report of its examination of DNA of 280 UK Kennel Club cavalier King Charles spaniels. Based upon the results of the study, AHT has estimated that 19.1% of the overall population of UK cavaliers are carriers of episodic falling syndrome. The study also included the CKCSs' curly coat syndrome. AHT estimates that 10.8% of cavaliers are carriers of curly-coat.

The EFS mutation was found nearly five times more frequently in wholecolors (rubies and black and tans) than in the particolors (Blenheims and tri-colors). The researchers concluded that19.1% of CKCSs are carriers of EFS, 35% of wholecolors (rubies and black-and-tans) are carriers, 0.3% of particolors (Blenheims and tri-colors) are affected with EFS, and 5.1% of wholecolors are affected.

AHT estimates that 1% to 2% of cavaliers carry both EFS and curly-coat. The entire report is available here.

May 2012: UK's Animal Health Trust reports interim results of DNA testing. The Animal Health Trust reported that, as of May 15, 2012: 2,811 cavaliers have been DNA-tested for episodic falling syndrome, of which 104 (3.7%) have been found to be "affected" with two of the mutated EFS gene; 605 (21.52%) are "carriers" with only one of the mutated gene; and the rest, 2,102 (74.78%), are clear of the defective gene.

January

2012: UK researchers identify

mutated gene causing episodic falling syndrome (EFS) in the cavalier.

Drs. Oliver P. Forman, Jacques Penderis (right), Claudia Hartley, Louisa J.

Hayward, Sally L. Ricketts, and Cathryn S. Mellersh of

the Animal Health Trust and University of Glasgow have identified a mutation of

the BCAN gene was associated with EFS in the CKCS.

See report below. They confirmed an identical finding by Drs.

Jennifer L. Gill, Kate L. Tsai, Christa Krey, Rooksana E. Noorai, Jean-François

Vanbellinghen, Laurent S. Garosi, G. Diane Shelton, Leigh Anne Clark,

and Robert J. Harvey, in

another

January 2012 study.

January

2012: UK researchers identify

mutated gene causing episodic falling syndrome (EFS) in the cavalier.

Drs. Oliver P. Forman, Jacques Penderis (right), Claudia Hartley, Louisa J.

Hayward, Sally L. Ricketts, and Cathryn S. Mellersh of

the Animal Health Trust and University of Glasgow have identified a mutation of

the BCAN gene was associated with EFS in the CKCS.

See report below. They confirmed an identical finding by Drs.

Jennifer L. Gill, Kate L. Tsai, Christa Krey, Rooksana E. Noorai, Jean-François

Vanbellinghen, Laurent S. Garosi, G. Diane Shelton, Leigh Anne Clark,

and Robert J. Harvey, in

another

January 2012 study.

July

2011: UK's LABOKLIN offers genetic test for

Episodic Falling Syndrome.

Researchers led by Dr. Robert Harvey

of the London School of Pharmacy, Dr. Leigh Anne Clark

(Clemson) and Dr. Diane Shelton (Univ.Cal. at San Diego) (right) have identified the underlying genetic defect

causing EFS in cavaliers. They found:

Researchers led by Dr. Robert Harvey

of the London School of Pharmacy, Dr. Leigh Anne Clark

(Clemson) and Dr. Diane Shelton (Univ.Cal. at San Diego) (right) have identified the underlying genetic defect

causing EFS in cavaliers. They found:

"Consistent with the unique clinical observed in affected dogs, we discovered that a homozygous microdeletion affecting BCAN is associated with EFS in CKCS dogs, confirming that this disorder is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. This mutation was not detected in control DNA samples from 54 other dog breeds, confirming the unique nature of this genomic rearrangement. ... Wider testing of a larger population of CKCS dogs without a history of EFS from the USA revealed that carriers are extremely common (12.9%). The development of molecular genetic tests for the EFS microdeletion will allow the implementation of directed breeding programs aimed at minimizing the number of animals with EFS and enable confirmatory diagnosis and pharmacotherapy of affected dogs."

See January 2012 report here for details. LABOKLIN's website for ordering the test kit is here.

April 2011: UK's Animal Health Trust begins offering a DNA test for EFS. Starting on April 18, the Animal Health Trust will offer to cavalier breeders a DNA swab test to detect the mutations causing episodic falling syndrome in their cavalier breeding stock. Go to AHT’s online DNA testing webshop for more details. The DNA test is available world-wide. Read more here.

February 2011: Dr. Penderis reports discovery of single gene causing EFS. Dr. Jacques Penderis reported at the 2011 Veterinary Ireland Conference and in an interview with Irish journalist Karlin Lillington that his reasearch team has identified a single recessive gene mutation causing EFS. He said that a genetic test for the gene should be released in the spring of 2011, probably in April.

November

2010: DNA Region for Episodic

Falling Syndrome Has Been Found. Animal Health Trust veterinary

geneticist Dr. Tom Lewis (right) announced at the UK Cavalier Club's

"Cavalier Health Day" on November 20 that the DNA region for the episodic

falling syndrome in cavaliers has been located. The AHT is continuing its

research to identify the precise mutations of gene(s) causing EFS. The

Trust's future plan is to offer a DNA test for the mutations to cavalier

breeders.

November

2010: DNA Region for Episodic

Falling Syndrome Has Been Found. Animal Health Trust veterinary

geneticist Dr. Tom Lewis (right) announced at the UK Cavalier Club's

"Cavalier Health Day" on November 20 that the DNA region for the episodic

falling syndrome in cavaliers has been located. The AHT is continuing its

research to identify the precise mutations of gene(s) causing EFS. The

Trust's future plan is to offer a DNA test for the mutations to cavalier

breeders.

April

2009: Dr. Penderis researches inheritance pattern of EFS in CKCSs.

Dr. Jacques Penderis

is conducting research

to try to establish the pattern of inheritance of

episodic falling in the cavalier. He is collecting pedigrees from affected dogs

for pedigree analysis, particularly where the disease status of related dogs

(e.g. parents and litter mates) are known.

to try to establish the pattern of inheritance of

episodic falling in the cavalier. He is collecting pedigrees from affected dogs

for pedigree analysis, particularly where the disease status of related dogs

(e.g. parents and litter mates) are known.

He reports that funding is now in place to perform a genome scan in the cavalier to try and identify the genetic region of interest responsible for episodic falling. Funding is still required for the fine sequencing to follow the genome scan. Anyone interested in contributing to these projects should contact Dr. Cathryn Mellersh (right) at the Animal Health Trust, email: Cathryn.Mellersh@ aht.org.uk

For this study Dr. Penderis is very interested in collecting blood samples or cheek swabs for DNA extraction from affected dogs, and normal related dogs. Dr. Penderis requires blood samples from known affected dogs and from as many normal related dogs as possible (particularly litter mates, parents, grandparents and offspring). The study's goal is to develop a genetic test to allow identification of the affected dogs and asymptomatic carriers, so that the disease may be totally eradicated from all tested breeding lines. Dr. Penderis may be contacted at Clinical Neurology / Neurosurgery Service, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Glasgow, Bearsden Road, Glasgow G61 1QH, Tel: +(44) 0141 330 5738 (office), Email: j.penderis@vet.gla.ac.uk

October

2007: Animal Health Trust team is to research episodic falling in CKCSs.

Dr.

Jacques Penderis (right) reported that he has teamed up with Dr. Cathryn

Mellersh of the Animal Health Trust and a graduate student, Oliver Forman, to

conduct a study of four canine neurological conditions, including episodic

falling in the CKCS. Also, Professor Robert Harvey, of The School of Pharmacy in

London. has proposed some "interesting candidate genes" for the cavaliers they

we will be jointly studying.

Dr.

Jacques Penderis (right) reported that he has teamed up with Dr. Cathryn

Mellersh of the Animal Health Trust and a graduate student, Oliver Forman, to

conduct a study of four canine neurological conditions, including episodic

falling in the CKCS. Also, Professor Robert Harvey, of The School of Pharmacy in

London. has proposed some "interesting candidate genes" for the cavaliers they

we will be jointly studying.

These candidate gene studies are in need of financial underwriting. Dr. Penderis estimates that it will cost £2,000 +/- for the candidate gene work, and there will be the sequencing costs to follow that, in excess of £6,000. Anyone interested in contributing to these projects should contact Dr. Cathryn Mellersh at the Animal Health Trust, email: Cathryn.Mellersh@aht.org.uk

RETURN TO TOP

Related Links

RETURN TO TOP

Veterinary Resources

Episodic falling in the Cavalier King Charles spaniel. Herrtage ME, Palmer AC. Veterinary Record 1983;112:458-459. Quote: Sudden collapse has been known to occur in this breed for at least 20 years. This report is based on 9 clinical cases and reports from several breeders and veterinary surgeons. Relief obtained by administering the neuroleptic diazepam was only temporary. The clinical signs were similar to those of "Scottie cramp". There was not yet any definite evidence of a genetic trait.

Muscle hypertonicity in the cavalier King Charles spaniel - myopathic features. Wright JA, Brownlie SE, Smyth JBA et al. Veterinary Record 1986;118:511-512.

A myopathy associated with muscle hypertonicity in the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel. Wright JA, Smyth JBA, Brownlie S, Robins M. J Com Path 1987;97:559-565. Quote: "Clinical signs of electrically silent muscle hypertonicity are described in five Cavalier King Charles dogs. Biopsies of the biceps femoris and triceps muscles, when examined with the electron miscroscope, revealed evidence of sarcotubular and mitochondrial abnormalities. These included enlargement of the sarcoplasmic reticulum, hydropic degeneration of mitochondria, tubular proliferations in the vicinity of the triads and vacuolar invagination of mitochondria. The exact nature of these findings is not clear and it is suggested that utilization of tracer techniques would help to explain them."

Low cerebrospianl fluid concentration of free gamma-aminobutyric acid in startle disease. Dubowitz LM, Bouza H, Hird MF, Jackson J. Lancet 1992;340:80-81.

Mutations in the alpha 1 subunit of the inhibitory glycine receptor cause the dominant neurologic disorder, hyperekplexia. Shiang R, Ryan S, Ya-Zhen Z et al. Nature Genetics 1993;5:351-358.

Update on Mitral Valve Disease. Jens Häggström and Clarence Kvart. Proc. 15th ACVIM Forum; 1997. Quote: "An interesting observation that may be of comparative interest is that Cavalier King Charles Spaniels have been shown to have a high prevalence (30%) of thrombocytopenia and macrothrombocytosis. Humans with MVP [mitral valve prolapse] tend to have shortened platelet survival times and thromboembolic episodes primarily in the retinal and cerebral circulation. Thromboembolic events in the retinal ore cerebral circulation may be involved in the disturbances described in the breed as 'episodic falling' and 'fly catching'."

Control of Canine Genetic Diseases. Padgett, G.A., Howell Book House1998, pp. 198-199, 234.

Hypertonicity in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. Shelton GD, Comparative Neuromuscular Lab, June 2001. Quote: "A syndrome of exercise-induced muscle hypertonicity was described several years ago in young Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (CKCS) from the UK. The history of exercise and excitement-induced 'collapse' was preceded by a 'deer-stalking' action with the head held close to the ground and the bottom high in the air. An increasingly stilted gait was observed until there was finally collapse to one side. An increase in extensor tone of the muscles of all four limbs was evident during the period of collapse. The time period required for recovery of limb function was usually about ten minutes. Mentation was not abnormal throughout the episodes. Electromyographic evaluation showed the muscles were electrically silent. While muscle biopsy specimens were not abnormal at the light microscopic level, rather non-specific ultrastructural abnormalities were observed. A similar syndrome has recently been identified in five CKCS dogs from the USA (three males, two females). Two of the dogs were from Ohio and one each were from Louisiana, Florida, and Illinois (See video clip). Age at clinical presentation ranged from two-seven months. These dogs showed very similar clinical presentations to the dogs originally described from the UK. Where evaluated, neither electrophyiological or histological abnormalities were identified. ... Clonazepam has been used in two affected CKCS dogs with reports of approximately 70-80% improvement suggesting a problem with GABA neurotransmission. Investigators at the Comparative Neuromuscular Laboratory at the University of California, San Diego are interested in being notified of any other possibly affected dogs."

Muscular dystrophies and other inherited myopathies. Shelton GD, Engvall E,Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2002; 32:103-124.

Hypertonicity in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. Garosi LS, Platt SR, Shelton GD. J Vet Intern Med 2002; 16:330. Quote: "A syndrome of exercise-induced muscle hypertonicity was described several years ago in young Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (CKCS) of common ancestry from the United Kingdom. Recently, 3 CKCS with very similar clinical presentations were evaluated in the UK and 4 dogs were identified in the USA. Age at presentation ranged from 4 to 7 months and both males and females were affected. A typical history included exercise and excitement-induced 'collapse' which was preceded by a 'deer-stalking' action with the head held close to the ground and the bottom high in the air. An increase in extensor tone of the muscles of all four limbs was evident prior to falling over and during the period of collapse. Mentation was not abnormal throughout the episodes. Hereditary hyperekplexia (also called startle disease), a syndrome described in humans, has a similar clinical presentation in which hypertonia may be elicited by unexpected auditory, visual, or sensory stimuli. Similar to the falling over that occurs in the CKCS, these attacks in humans may result in unchecked falling despite complete retention of consciousness. Hyperekplexia in humans responds dramatically although not completely to the benzodiazepine drug clonazepam, which enhances gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmission. Low levels of CSF GABA have been reported in human patients. Following extensive neurological and neuromuscular evaluations that resulted in no specific abnormalities, a treatment trial with oral clonazepam (0.5 mg/kg TID) was performed in 2 affected CKCS dogs in the UK and 2 dogs in the USA. All 4 dogs responded dramatically to clonazepam therapy. Episodes of hypertonicity decreased from 25–30 per week to 1 every 2–3 months. after 2 years of therapy with clonazepam, the 2 dogs from the USA were described as clinically normal with only infrequent episodes. Although the inciting stimuli differ, the response to clonazepam therapy suggests a similar underlying disorder of GABA neurotransmission in the CKCS dogs and human hyperekplexia patients."

Clinical Neurology in Small Animals - Localization, Diagnosis and Treatment. K.G. Braund, International Veterinary Information Service, Ithaca, New York, USA; Paroxysmal Disorders (6-Feb-2003). Quote: "Episodic falling or hypertonicity is a well-recognized paroxysmal disorder in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels in the UK, and has been seen in the United States and Australia." www.ivis.org/special_books/Braund/braund29/ivis.pdf

A rare syndrome in cavaliers. G. Diane Shelton. AKC Gazette. Apr. 2003:24. Quote: "Dr. G. Diane Shelton, of the University of California at San Diego, reported on the treatment of several Cavalier King Charles Spaniels diagnosed with exercise- induced muscle hypertonicity. This syndrome was described several years ago in dogs from the United Kingdom, but seven cases that were identified recently included four dogs in the United States. Male and female Cavalier pups with a history of exercise- or excitement-induced collapse had been presented. They were between 4 and 7 months of age at the time. Exactly when the symptoms began is unclear. A typical event of this syndrome begins with activity that looks like stalking: The dog holds its head to the ground with its hindquarters up in the air. As the event progresses, the legs straighten and become tense, which ultimately causes collapse. Mentally, the dog remains normal. It knows what is happening and apparently sees clearly, but seems to lose control of its body. After extensive tests that yielded no specific abnormalities, two of the U.S. dogs and two of the U.K. dogs were treated with clonazepam, the drug commonly used to treat people with a similar syndrome called hereditary hyperekplexia (or startle disease) . With treatment, episodes decreased in frequency from between 25 and 30 each week down to one every two to three months. After two years of clonazepam, the two U.S. dogs were described as clinically normal. Episodes were infrequent."

Breed Predispositions to Disease in Dogs & Cats. Alex Gough, Alison Thomas. 2004; Blackwell Publ. 44-45.

Neurological diseases of the Cavalier King Charles spaniel. Rusbridge, C. J Small Animal Practice, 30 June 2005, 46(6): 265-272.

Efficient mapping of mendelian traits in dogs through genome-wide association. Elinor K Karlsson, Izabella Baranowska, Claire M Wade1, Nicolette H C Salmon Hillbertz, Michael C Zody, Nathan Anderson, Tara M Biagi, Nick Patterson, Gerli Rosengren Pielberg, Edward J Kulbokas III, Kenine E Comstock, Evan T Keller, Jill P Mesirov, Henrik von Euler, Olle Kämpe, Åke Hedhammar, Eric S Lander, Göran Andersson, Leif Andersson, Kerstin Lindblad-Toh. Nature Genetics. Sept. 2007;39:1321 - 1328. Quote: "With several hundred genetic diseases and an advantageous genome structure, dogs are ideal for mapping genes that cause disease. Here we report the development of a genotyping array with ~27,000 SNPs and show that genome-wide association mapping of mendelian traits in dog breeds can be achieved with only ~20 dogs. Specifically, we map two traits with mendelian inheritance: the major white spotting (S) locus and the hair ridge in Rhodesian ridgebacks. For both traits, we map the loci to discrete regions of <1 Mb. Fine-mapping of the S locus in two breeds refines the localization to a region of ~100 kb contained within the pigmentation-related gene MITF. Complete sequencing of the white and solid haplotypes identifies candidate regulatory mutations in the melanocyte-specific promoter of MITF. Our results show that genome-wide association mapping within dog breeds, followed by fine-mapping across multiple breeds, will be highly efficient and generally applicable to trait mapping, providing insights into canine and human health."

A Practical Guide to Canine and Feline Neurology. Curtis W. Dewey. John Wiley & Sons; 2008; 4-6, 482-483. Quotes: "Breed-associated neurologic abnormalities of dogs and cats. ... Cavalier King Charles Spaniels ... Episodic muscle hypertonicity ("falling cavaliers" -- probable dyskinesia" pg. 4-6. ""An age range ... has been reported of ... 14 weeks to 4 years for Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. ... Crossing of the thoracic limbs over the top of the head has been described in collapsing Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. ... Cavalier King Charles Spaniels tend to be less responsive to diaaepam than other breeds with the condition, but they can markedly improve with clonazepam treatment. Tolerance to clonzepam may develop in the long term. Other therapies reported to decrease frequency and severity of episodes include vitamin E and tryptophan. This is a nonprogressive disorder that tends to improve with therapy. Life spans of affected dogs do not appear to be shortened by the disease." pp. 482-483.

A canine DNM1 mutation is highly associated with the syndrome of exercise-induced collapse. Patterson EE, Minor KM, Tchernatynskaia AV, Taylor SM, Shelton GD, Ekenstedt KJ, Mickelson JR. Nat Genet 2008; 40:1235-1239.

Muscular dystrophy in Cavalier King Charles spaniels. Piercy, Richard. J. and Walmsley, Gemma. Vet Rec. 2009 165 (2), p. 62. Quote: "We have recently identified the genetic cause of a form of muscular dystrophy in CKCS. The causative mutation is in the dystrophin gene and the X-linked disease is associated with weakness, muscle atrophy and exercise intolerance, detectable from a few months of age. Prominent signs in affected dogs are dysphagia [the symptom of difficulty in swallowing] and macroglossia (enlarged tongue)[tongue enlargement that leads to functional and cosmetic problems]. Serum creatine kinase is usually markedly elevated. Male dogs with the mutation [are] clinically affected and female dogs with the mutation are silent carriers. We are also keen to hear from veterinary surgeons who believe they may have seen an affected dog in their practice, in order to estimate the prevalence of this disease and limit its spread by genetic testing." Contact Dr. Piercy at the Royal Veterinary College's Comparative Neuromuscular Diseases Laboratory at rpiercy@rvc.ac.uk

Breed Predispositions to Disease in Dogs & Cats (2d Ed.). Alex Gough, Alison Thomas. 2010; Wiley-Blackwell Publ. 52.

Update: Mutation Identified in Episodic Falling Syndrome in Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Dogs. Dr. Diane Shelton. Comparative Neuromuscular Lab, March 2011. Quote: "Almost 30 years ago a syndrome of exercise-induced muscle hypertonicity and falling (Episodic Falling, EFS) was described in young Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (1-3, and June 2001 Case of the Month). Clinical signs included exercise and excitement-induced “collapse” that was preceded by a “deer-stalking” action with the head held close to the ground and the bottom high in the air. An increasingly stilted gait was observed until there was finally collapse to one side. An increase in extensor tone in the muscles of both the thoracic and pelvic limbs was present during the period of collapse. The time period required for recovery of limb function was usually about 10 minutes. Mentation was normal throughout the episodes. Electromyographic evaluation showed the muscles were electrically silent. Dogs were neurologically normal between episodes. A microdeletion in the central nervous system gene BCAN1 has been shown to be highly associated with EFS in CKCS dogs and a scientific paper recently published (4). The carrier rate was approximately 13% suggesting that the EFS microdeletion is present at a high frequency in the general CKCS population. Molecular genetic testing for the EFS microdeletion is now available through Laboklin. Information regarding testing can be found here."

Genetic Connection: A Guide to Health Problems in Purebred Dogs, Second Edition. Lowell Ackerman. July 2011; AAHA Press; pg 120. Quote: "Episodic falling is an autosomal recessive disorder of muscle innervation reported in the Cavalier King Charles spaniel. It is often detected in affected animals in their first year of life, when they are unable to relax, their muscles become rigid and they fall over. Typical triggers are exercise, excitementt, or frustration. Fortunately, DNA testing is available to detect clear, carrier, and affected animals."

New DNA tests for Cavalier King Charles spaniels. Vet Rec 2011 168(14):370. "NEW DNA tests to detect the mutations causing congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform dermatosis (dry eye and curly coat syndrome) and episodic falling in Cavalier King Charles spaniels will be available from the Animal Health Trust (AHT) later this month. Episodic falling is a neurological condition induced by exercise, excitement or frustration. The dog's muscle tone increases and the animal is unable to relax its muscles, becomes rigid and falls over. Dry eye and curly coat syndrome results in an affected dog producing no tears, so its eyes become sore. The skin becomes flaky and dry, particularly around the feet, which can make standing and walking difficult and painful. The syndrome appears to be unique to Cavalier King Charles spaniels and most dogs diagnosed with it are euthanased. Researchers at the Kennel Club Genetics Centre at the AHT have now identified the mutations responsible for the two conditions. This has allowed the development of the new DNA tests, which will be available from the AHT from April 18. Cathryn Mellersh, head of canine genetics at the AHT, said: To date there has been no long-term effective treatment for either dry eye and curly coat syndrome or episodic falling so the development of the DNA tests is an important breakthrough for breeders and owners of Cavalier King Charles spaniels. As with all inherited disease, it's important that breeders are armed with the facts and that they still continue to use carrier dogs in their breeding programmes. Breeding a carrier with a non-carrier will not produce affected puppies; however, breeding just clear dogs with other clear dogs could reduce the gene pool within the breed and this could lead to other health problems in the future."

A canine BCAN microdeletion associated with Episodic Falling Syndrome. Jennifer L. Gill, Kate L. Tsai, Christa Krey, Rooksana E. Noorai, Jean-François Vanbellinghen, Laurent S. Garosi, G. Diane Shelton, Leigh Anne Clark, and Robert J. Harvey. Neurobiology of Disease. Jan 2012;45(1):130-136. Quote: "Episodic falling syndrome (EFS) is a canine paroxysmal hypertonicity disorder found in Cavalier King Charles spaniels. Episodes are triggered by exercise, stress or excitement and characterized by progressive hypertonicity throughout the thoracic and pelvic limbs, resulting in a characteristic 'deer-stalking' position and/or collapse. We used a genome-wide association strategy to map the EFS locus to a 3.48 Mb critical interval on canine chromosome 7. By prioritizing candidate genes on the basis of biological plausibility, we found that a 15.7 kb deletion in BCAN, encoding the brain-specific extracellular matrix proteoglycan brevican, is associated with EFS. This represents a compelling causal mutation for EFS, since brevican has an essential role in the formation of perineuronal nets governing synapse stability and nerve conduction velocity. ... Consistent with the unique clinical signs observed in affected dogs, we discovered that a homozygous microdeletion affecting BCAN is associated with EFS in CKCS dogs, confirming that this disorder is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. This mutation was not detected in control DNA samples from 54 other dog breeds, confirming the unique nature of this genomic rearrangement. ... Certainly, since EFS appears to result from a central nervous system rather than a muscle defect, the associated sarcoplasmic reticulum pathology is likely to be a secondary manifestation of muscle overstimulation. ... Mapping of the deletion breakpoint enabled the development of Multiplex PCR and Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification (MLPA) genotyping tests that can accurately distinguish normal, carrier and affected animals. Wider testing of a larger population of CKCS dogs without a history of EFS from the USA revealed that carriers are extremely common (12.9%). The development of molecular genetic tests for the EFS microdeletion will allow the implementation of directed breeding programs aimed at minimizing the number of animals with EFS and enable confirmatory diagnosis and pharmacotherapy of affected dogs."

Parallel Mapping and Simultaneous Sequencing Reveals Deletions in BCAN and FAM83H Associated with Discrete Inherited Disorders in a Domestic Dog Breed. Oliver P. Forman, Jacques Penderis, Claudia Hartley, Louisa J. Hayward, Sally L. Ricketts, and Cathryn S. Mellersh. PLoS Genet. 2012 January; 8(1): e1002462. Quote: "The domestic dog (Canis familiaris) segregates more naturally-occurring diseases and phenotypic variation than any other species and has become established as an unparalled model with which to study the genetics of inherited traits. We used a genome-wide association study (GWAS) and targeted resequencing of DNA from just five dogs to simultaneously map and identify mutations for two distinct inherited disorders that both affect a single breed, the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel. We investigated episodic falling (EF), a paroxysmal exertion-induced dyskinesia, alongside the phenotypically distinct condition congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform dermatosis (CKCSID), commonly known as dry eye curly coat syndrome. EF is characterised by episodes of exercise-induced muscular hypertonicity and abnormal posturing, usually occurring after exercise or periods of excitement. CKCSID is a congenital disorder that manifests as a rough coat present at birth, with keratoconjunctivitis sicca apparent on eyelid opening at 10–14 days, followed by hyperkeratinisation of footpads and distortion of nails that develops over the next few months. We undertook a GWAS with 31 EF cases, 23 CKCSID cases, and a common set of 38 controls and identified statistically associated signals for EF and CKCSID on chromosome 7 (Praw 1.9×10-14; Pgenome=1.0×10-5) and chromosome 13 (Praw 1.2×10-17; Pgenome=1.0×10-5), respectively. We resequenced both the EF and CKCSID disease-associated regions in just five dogs and identified a 15,724 bp deletion spanning three exons of BCAN associated with EF and a single base-pair exonic deletion in FAM83H associated with CKCSID. Neither BCAN or FAM83H have been associated with equivalent disease phenotypes in any other species, thus demonstrating the ability to use the domestic dog to study the genetic basis of more than one disease simultaneously in a single breed and to identify multiple novel candidate genes in parallel."

Frequency of two disease-associated mutations in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, June 2012. Animal Health Trust. Quote: "In 2012 scientists at the Kennel Club Genetics Centre at the Animal Health Trust undertook a study to measure the frequency of the mutations responsible for congential keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform dermatosis (dry eye and curly coat syndromd) and episodic falling in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels in the UK. This report describes the study, its conclusions and recommendations for breeders."

Investigation of two disorders in the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel. Chapter 3 of "Advances in genetic mapping and sequencing techniques: a demonstration using the domestic dog model." Oliver Forman PhD thesis pp.63-102, University of Glasgow. 2013.

Phenotypic characterisation of canine epileptoid cramping syndrome in the border terrier. V. Black, L. Garosi, M. Lowrie, R. J. Harvey, J. Gale. J Small Anim Pract. January 2014;55(1):102–107. Quote: Objectives: To characterise the phenotype of Border terriers suspected to be affected by canine epileptoid cramping syndrome and to identify possible contributing factors. Methods: Owners of Border terriers with suspected canine epileptoid cramping syndrome were invited to complete an online questionnaire. The results of these responses were collated and analysed. Results: Twenty-nine Border terriers were included. Most affected dogs had their first episode before 3 years of age (range: 0·2 to 7·0 years). The majority of episodes lasted between 2 and 30 minutes (range: 0·5 to 150 minutes). The most frequent observations during the episodes were difficulty in walking (27 of 29), mild tremor (21 of 29) and dystonia (22 of 29). Episodes most frequently affected all four limbs (25 of 29) and the head and neck (21 of 29). Borborygmi were reported during episodes in 11 of 29 dogs. Episodes of vomiting and diarrhoea occurred in 14 of 29, with 50% of these being immediately before or after episodes of canine epileptoid cramping syndrome (7 of 14). Most owners (26 of 29) had changed their dog's diet, with approximately 50% (14 of 26) reporting a subsequent reduction in the frequency of episodes. Clinical Significance: This study demonstrates similarities in the phenotype of canine epileptoid cramping syndrome to paroxysmal dystonic choreoathetosis, a paroxysmal dyskinesia reported in humans. This disorder appears to be associated with gastrointestinal signs in some dogs and appears at least partially responsive to dietary adjustments.

Canine Paroxysmal Movement Disorders. Ganokon Urkasemsin, Natasha J. Olby. Vet. Clinics of No. Amer.: Small Animal Pract. Nov. 2014;44(6):1091-1102. Quote: "Paroxysmal dyskinesias are episodic movement disorders characterized by muscle hypertonicity that can produce involuntary movements. Signs emanate from the central nervous system; consciousness is not impaired, ictal electroencephalography is normal, and there are no autonomic signs, distinguishing them from seizure disorders. In humans they are classified into 3 groups, each responding to different therapies. A mutation in the gene for brevican (BCAN) has been identified as the cause of Episodic Falling in Cavalier King Charles spaniels. Further elucidation of the genetic causes will enhance our ability to identify and treat these canine diseases."

Dystonia and Paroxysmal Dyskinesias: Under-Recognized Movement Disorders in Domestic Animals? A Comparison with Human Dystonia/Paroxysmal Dyskinesias. Angelika Richter, Melanie Hamann, Jörg Wissel, Holger A. Volk. Frontiers in Vet. Sci. November 2015. Quote: "Generalized Movement Disorders Which Possibly Include Dystonic Features -- Paroxysmal Dyskinesias in Dogs -- Episodic falling in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (CKCS), an autosomal-recessive inherited disorder, shares similarities with human paroxysmal dyskinesia. In affected dogs, exercise and excitement can precipitate episodes of abnormal gait and fallings which last up to several minutes. There are no signs of an impairment of consciousness or autonomic dysfunction during or after these attacks. Affected animals develop an increased extensor muscle tone of all four limbs, resulting in an immobilized, “deer-stalking” or “praying” position, sometimes falling with legs held in extensor rigidity. Other clinical signs are facial muscle stiffness, stumbling, a 'bunny-hopping' gait, and arching of the back. It is unclear if cocontractions of flexors are involved. Initial clinical signs of the disease typically appear between 3 and 7 months of age. Interestingly, in some cases, there is spontaneous remission, as sometimes observed in human paroxysmal dyskinesia. There is no evidence for metabolic alterations as a cause, and light microscopic examinations have not revealed any lesions in the CNS or peripheral nerves. Clonazepam may be effective in suppressing the episodes in some cases. Recently, a 15.7 kb deletion in BCAN, encoding the brain-specific extracellular matrix-proteoglycan brevican, was found to be associated with episodic falling in CKCS. This protein plays an important role in cell adhesion, migration, axon guidance, and neuronal plasticity. How this mutation leads to the manifestation of this hyperkinetic movement disorder in dogs has yet to be unraveled."

The Clinical and Serological Effect of a Gluten-Free Diet in Border Terriers with Epileptoid Cramping Syndrome. M. Lowrie, O.A. Garden, M. Hadjivassiliou, R.J. Harvey, D.S. Sanders, R. Powell, L. Garosi. J. Vete. Intern. Med. November 2015;29(6):1564-1568. Quote: Background: Canine epileptoid cramping syndrome (CECS) is a paroxysmal movement disorder of Border Terriers (BTs). These dogs might respond to a gluten‐free diet. Objectives: The objective of this study was to examine the clinical and serological effect of a gluten-free diet in BTs with CECS. Animals: Six client-owned BTs with clinically confirmed CECS. Methods: Dogs were prospectively recruited that had at least a 6-month history of CECS based on the observed phenomenology (using video) and had exhibited at least 2 separate episodes on different days. Dogs were tested for anti-transglutaminase 2 (TG2 IgA) and anti-gliadin (AGA IgG) antibodies in the serum at presentation, and 3, 6, and 9 months after the introduction of a gluten-free diet. Duodenal biopsies were performed in 1 dog.

Long-term treatment of canine paroxysmal dyskinesias with fluoxetine: 6 cases. T. Bouzouraa, C. Escriou. ESVN Abstract J. Vet. Int. Med. December 2015. Quote: "It is only recently that both clinical features and genetic basis of canine paroxysmal dyskinesias (CPDs) have been documented. Their management remains challenging though phenothiazine, benzodiazepines even anticonvulsants yielded unsatisfactory results. Fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, seems promising. Three Scottish terriers (STs), 2 Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (CKCSs) suffering from Scottie Cramp (SC) and Episodic Falling, respectively, then an English Setter with a dyskinesia of unknown origin, displayed many daily episodes, triggered by exercise and/or excitement that definitely preventing them from living normally. All dogs received fluoxetine as a single treatment (2–4 mg/kg q24 h). Four dogs displayed early and complete remissions that persisted over long periods (1 year for 1 CKCS then 2, 6 and 7 years for the 3 STs). The remaining 2 cases showed a significant improvement with a decline to approximately one single episode every 2 months for both dogs. Transient relapses occurred when treatment was interrupted or tapered in 3 dogs. No treatment resistance or side effect was observed. Fluoxetine may be a good and safe option for the long-term management of CPDs, allowing dogs for resuming to normal activity and lifestyle. It can directly correct serotoninergic transmission imbalance suspected in SC. Its activity remains unclear in other CPDs; direct serotoninergic action is likely but indirect effect through a reduction of behavioral reactivity to triggering factors like stress, excitation or environmental stimulations is also plausible."

Natural history of canine paroxysmal movement disorders in Labrador retrievers and Jack Russell terriers. Mark Lowrie, Laurent Garosi. Vet. J. July 2016;213:33-37. Quote: In dogs, the first genetically mapped PD [paroxysmal dyskinesia] was that associated with EFS [episodic falling syndrome] in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (Forman et al., 2012; Gill et al., 2012). The mutation was characterised as a deletion affecting the brevican gene (BCAN) which encodes a brain-specific component of the extracellular matrix proteoglycan complex. It is thought to be involved in homeostasis and mutations of this protein result in a disruption of axonal conduction and synaptic stability. An interesting observation in EFS is that the condition is self-limiting in some cases (Forman et al., 2012). It is suggested that compensatory pathways involving up regulation of other proteoglycans may occur and account for this rectification. Dogs in our study also seemed to show this improvement with age so a similar compensatory mechanism may be considered.

Frequency estimation of disease-causing mutations in the Belgian population of some dog breeds - Part 2: retrievers and other breed types. E. Beckers, M. Van Poucke, L. Ronsyn, L. Peelman. Vlaams Diergeneeskundiig Tijdschrift. October 2016:185-196. Quote: A Belgian population of ten breeds with a low to moderately low genetic diversity or which are relatively popular in Belgium, i.e. Bichon frise, Bloodhound, Bouvier des Flandres, Boxer, Cavalier King Charles spaniel, Irish setter, Papillon, Rottweiler, Golden retriever and Labrador retriever, was genotyped for all potentially relevant disease-causing variants known at the start of the study. In this way, the frequency was estimated for 26 variants in order to improve breeding advice. Disorders with a frequency high enough to recommend routine genotyping in breeding programs are (1) degenerative myelopathy for the Bloodhound, (2) arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and degenerative myelopathy for Boxers, (3) episodic falling syndrome and macrothrombocytopenia for the Cavalier King Charles spaniel, (4) progressive retinal atrophy rod cone dysplasia 4 for the Irish setter (5) Golden retriever progressive retinal atrophy 1 for the Golden retriever and (6) exercise induced collapse and progressive rod-cone degeneration for the Labrador retriever. To the authors’ knowledge, in this study, the presence of a causal mutation for a short tail in the Bouvier des Flandres is described for the first time. ... The autosomal recessive disorder episodic falling syndrome (EFS) causes neurological episodes often triggered by stress, excitement or exercise. Symptoms occur at the age of three months to four years and become progressively worse. A frequency of 12.3% (Wt/Mt) carriers was found in 57 genotyped animals, which is very similar to the estimate of 12.9% carriers in a USA population (Gill et al., 2011). No homozygous mutant individuals were encountered (Table 3). The authors encourage routine genotyping in breeding dogs because of the high frequency.